by Fiona Passmore

As a primary school teacher with symbrachydactyly, Felicity understands only too well how awkward it might be for children with a hand difference starting a new school or class. She has kindly shared her personal and professional experiences and advice with us.

Felicity lives in Sydney and started primary school teaching about ten years ago after a long career in customer relations and marketing with Qantas. But until she taught a young girl with a hand difference in one of her kindy classes, she had never met anyone with a hand similar to hers. The two bonded instantly and were delighted to find that they shared many experiences and feelings about their hands.

In her classroom, Felicity encourages students to ask questions about her hand and acknowledges their feelings. Comments about her fingers looking like toes, and questions as to whether they will grow later or are painful are some of the more common ones.

‘Until I started teaching, I didn’t talk to people about my hand. As a child, no-one in my family knew how to address it, so consequently I didn’t learn any skills to help me,’ she recalled. ‘During my ten years in this profession, only one other teacher has asked about my hand. They are used to handling children with autism, ADHD or other more common needs, but strangely still don’t seem comfortable asking about a hand difference. Perhaps this is a lack of experience, education or training, but I’d love to see the younger generation of teachers being more open, but this hasn’t been my experience so far,’ she explained.

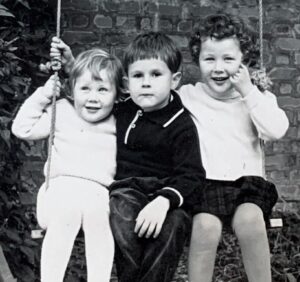

Felicity (far right)

As a teacher, Felicity’s mantra with all children is ‘assume capability’. Her approach with children who have a limb difference is to say, ‘I know your hand is a bit different and you can do lots of things, but if there’s anything you need help with, please let me know.’ She is always thinking about what might have helped her at school when she was a child and lets that guide her interactions with students.

Seeing people with differences portrayed in media and literature helps normalise those differences so Felicity loves using picture books to explain differences to her students. She notes, however, that it’s always important to be sensitive to how children feel about talking to others. More confident children might be happy to stand in front of their classmates and discuss their difference, while those who are a bit more reserved may prefer to have their teacher explain it. ‘Always ask the child and be guided by their preferences,’ she recommended.

Felicity painting her nails

Teachers should keep in mind that some children may develop unusual thoughts concerning their limb difference. ‘As a little girl, I thought I couldn’t get married because I didn’t have a left finger to put a wedding ring on,’ Felicity remembered. Open conversations around limb differences which focus on what the child can do are the key to helping them develop a positive view of themselves, their abilities and their future.

Felicity has noticed that, after school holidays, the five- and six-year-olds she teaches are always interested to see if her fingers have grown back during the break. ‘At that age, they’re aware of how much they’re growing so they assume my fingers will do the same, even though I’ve explained that they won’t,’ she smiled.

‘When it comes to addressing a child’s hand difference at school or in new situations, it can be hard to strike a sensitive balance,’ Felicity said. ‘Preparation can help them work out how to manage the questions and interest they’ll inevitably encounter but you also want to avoid making them feel that their difference is a problem. Each child is unique and will come to school with different feelings about their limb difference. If parents have been able to help them feel comfortable and confident, they’ll be well-placed to manage the questions and attention from their classmates. By providing warm, calm support and tapping into online resources, parents can help boost their child’s self-esteem and support them to educate others,’ she added.

Negative and positive interactions have lasting impressions on children and Felicity believes some awkward activities in schools – such as asking children to hold each other’s hands while walking as a group – could be avoided. She remembers this making her feel really uncomfortable as a youngster, especially when other children were reluctant to cooperate.

‘Parents can’t fix the world for their children or control what other people say or do, but they can build their child up so they are able to deal with the situations they’ll encounter, particularly in their formative years. Parents’ tone of voice and body language are really important. Be positive and try to manage your own emotions so you can support your child with theirs,’ she advised. ‘My mum was great, but I remember her crying about my hand, which made me feel awful,’ she added. A disability or difference is one thing, but how the person feels about it is something separate and there’s so much we can do to help children feel good about their difference and to help develop their resilience.

Felicity (far right) with husband Frank and daughter Annabel

‘When it comes to starting school, I suggest parents ask to speak in person to the Principal or Vice Principal, depending on the structure and size of the school. Ideally, you should also make an appointment to meet your child’s teacher, but if that’s not possible, with the Assistant Principal in charge of the Prep, Foundation or Kindy classes. This gives you the chance to explain your child’s difference, what it looks like (take in a photo) and any name the family may use for it (such as ‘nubby’, ‘little hand’ or ‘lucky fin’). You can then talk about all the things your child can do and activities they find hard or which may need to be adapted for them. This not only helps your child but prepares the teacher who will then be better equipped to handle questions from curious classmates,’ she recommended.

Felicity has twin sons and a daughter, now in their twenties. She breastfed her twin sons and didn’t give it a second thought but found out later, through chats with other mums in her local Twins Club, that the nurses at the hospital where she gave birth were in awe of her ability to do this. No-one at the hospital made any comment at the time, though. Is this another example of people keeping quiet because they aren’t sure what’s appropriate to say without causing offence or coming across as patronising?

‘The Aussie Hands Resource Toolkit is fantastic,’ said Felicity. ‘I wish something like this had been available to my parents when I was a child.’

The resource toolkit provides a wealth of tips, experiences, books, movies etc to help you and your child through the various stages of life. Whether it’s about starting school, making friends, participating in extracurricular activities, managing shoelaces, buttons or tying hair, please check it out on our website.

Many thanks to Felicity for sharing these valuable insights with our readers.